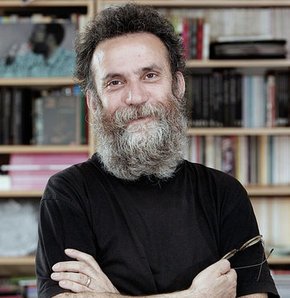

We are so pleased to be launching Haydar Ergülen's Selected Poems, Pomegranate Garden with UK launch events planned in London, Cardiff and Oxford this month (22 - 25 November). Haydar is one of the most prominent poets writing in Turkey today. Author of more than a dozen books of poetry and another dozen of essays, his work is only beginning to appear in English and this selected works will change his reach significantly. His most recent book is Öyle Küçük Şeyler (Kırmızı Kedi, 2016). He lives in Istanbul.

The poetry of Haydar Ergülen unquestionably draws upon and expresses many of the basic forces that continue to shape Turkish culture and literature; however, as with most of the best poetry produced anywhere, its central focus is the common, down-to-earth concerns of humanity itself. At the core of Ergülen’s work is the pervasive sense of poetry-writing as an inseparable part of life: that the co-existence of poetry, goodness and love is indispensable to the poet as a human being.

Edited by Mel Kenne, Saliha Paker and Caroline Stockford.

The poems have been translated by Mel Kenne, Saliha Paker, Caroline Stockford, Arzu Akbatur, Gökçenur Ç, Nilgün Dungan, Arzu Eker Roditakis, Clifford Endres, İdil Karacadağ, Elizabeth Pallitto, Selhan Savcıgil Endres, İpek Seyalıoğlu, and Şehnaz Tahir Gürçağlar.

Join us at one of the following free events on his UK book launch tour:

- Friday 22 – Turkish Studies & London Middle East Institute, SOAS, London, 12-2pm

- Sunday 24 – 10 Poems for Haydar Ergülen, St. Canna's Ale House, 42 Llandaff Road, Cardiff CF11 9NJ, 12-3pm

- Monday 25 – Board Room, the Middle East Centre, St Antony’s College, Oxford University, 5pm

Haydar Ergülen was born in Eskişehir, Turkey, in 1956. He published his first political and cultural broadside paper, Ekin (Culture), with his friend Şahin Şencan, when they were in middle school. At the age of eighteen he wrote articles protesting the death by capital punishment of political activists Deniz Gezmiş, Hüseyin İnan and Yusuf Aslan, activities that led to his month-long confinement by the police and expulsion from high school. He later took a degree in Sociology from Middle Eastern Technical University and held the position of teaching assistant in the Communications Faculty of Eskişehir Anadolu University while pursuing a Master’s Degree in marketing and public relations. In 1983 he moved to Istanbul and began writing advertising copy.

His first poems and short stories were published in 1972 in the Eskişehir magazine Deneme (Essay). In 1981 he placed second after the renowned poet Murathan Mungan in Hürriyet Gösteri magazine’s poetry competition, and his poetry began to appear in such magazines as Somut, Felsefe Dergisi, Türk Dili, Yusufçuk, Hürriyet Gösteri, Yarın, Yeni Biçem, Akatalpa, Sombahar, Nar, Yasak Meyve, Budala, Öküz, Hayvan, Ot, Bavul, Şiir-lik, Kitap-lık, Heves and Varlık.

Ergülen’s first book of poetry, Karşılığını Bulamamış Sorular (Questions Without Response), came out in 1981 and was followed in 1983 by his publication, along with poet-friends Adnan Özer and Tuğrul Tanyol, of Üç Çiçek (Three Flowers), which was recognised as the first magazine of Turkey’s ‘1980s-Era Poets.’ From 1986 onwards he contributed to the editorial board of Şiir Atı magazine, and went on to work with Eskişehir friends Rahmi Emeç and Erol Büyükmeriç on the editorial board of Yazılıkaya Şiir Yaprağı.

From 1998 to 2007 Ergülen wrote the column ‘Open Letters’ for the left-wing dailyRadikal and contributed to the daily BirGün. From 2010 to 2012 he wrote regularly for Cumhuriyet newspaper. He continues to write for BirGün’s Sunday supplement.

Ergülen is now serving as Director of the Izmir International Poetry Festival, the Eskişehir Tepebaşı International Poetry Festival, and the Nazım Hikmet International Poetry Event, organised by Ataşehir Municipality in Istanbul. He attends poetry festivals and translation workshops throughout Europe and leads creative writing workshops in Istanbul. For the last seven years Ergülen has taught Contemporary Poetry at Boğaziçi University, lectured on poetry at Kadir Has and Bahçeşehir universities, and given public lectures each month in Eskişehir.

Ergülen continues to write poetry and short stories, and twenty-one books of his poetry, including two written especially for children, have been published in Turkey, while two collections of his work (Carnet intime and Grenade / Nar, translated by Claire Lajus) have been published in France, with German, Italian and Bulgarian editions due to come out soon. In addition to these, numerous books of his criticism and essays, along with three anthologies that he edited, have been published since 2000.

Ergülen and his wife Idil have a daughter, Nar, and four cats. Gülten Akın, Özdemir İnce, Ece Ayhan, Ahmet Telli, Veysel Öngören, Metin Altıok, Enis Batur, Murathan Mungan, Salih Bolat and Ali Cengizkan are the poets he knew and liked in his years in Ankara. His favourite poets are Yunus Emre, Pir Sultan Abdal, Nazım Hikmet, Cemal Süreya, Ergin Günçe, and Federico Garcia Lorca. He also greatly admires the Anatolian folk singers Aşık Veysel, Aşık Mahzunî Şerif, and Neşet Ertaş.

Awards

- 1981 Hürriyet Gösteri magazine poetry prize (2nd) Unutulmuş Bir Yaz İçin 1996 Halil Kocagöz Poetry Prize – Eskiden Terzi

- 1997 Behçet Necatigil Poetry Prize – 40 Şiir ve Bir

- 1997 Cahit Külebi Special Prize at Orhon Murat Arıburnu Awards – 40 Şiir ve Bir1998 Akdeniz Altın Portakal Poetry Prize – 40 Şiir ve Bir

- 2005 Cemal Süreya Poetry Prize – Keder Gibi Ödünç

- 2008 Metin Altıok Poetry Prize – Üzgün Kediler Gazeli

- 2015 Honorary Prize of the Language Association (Dil Derneği) 2017 City of Mersin Prize for Literature

For more of an introduction to Haydar's work here is the foreword from the new book, written by editor Saliha Paker:

This first selection of Haydar Ergülen’s poetry to be presented to the English-speaking public is composed of poems picked out by the poet himself from his earliest collection in 1982 to his most recent one in 2019, and it includes a wide range of lyrical, narrative, and epigrammatic works. Ergülen is considered a leading figure of the 1980s generation of Turkish poets, one who is among the most representative of its poetic characteristics 1, while holding fast to his unique aspirations. We hope, therefore, that readers will emerge from this book with a clear view of how his poetry has evolved and an appreciation of why it has remained fresh over the years, maintaining its hold over its Turkish followers, young and old alike, since the early 1980s.

Haydar Ergülen’s poetry unquestionably draws upon and expresses many of the basic forces that continue to shape Turkish culture and literature; however, its central focus is the common, down-to-earth concerns of humanity itself. At the core of Ergülen’s work is the pervasive sense of poetry-writing as an inseparable part of life: that the co- existence of poetry, goodness and love is indispensable to the poet as a human being.

Approximately a third of the poems in our selection were translated at two workshops 2 held in 2006 and in 2013, while the rest of the translations were carried out in preparation for this book in consultation with the original team of translators. Ergülen was invited to participate as guest poet to both of the workshops. In a talk at the first workshop in 2006, Ergülen defined his poetry as one of nasip, his ‘lot in life’:

A poet should write with few words and, if possible repeat a word more than once. ‘Oh fall to my share,’ he should implore, and should believe that each word is indeed his lot, so he should leave other words for someone else, for others too to have their share of words...

I believe in nasip even as I ‘aspire’ to write poetry. Each poem, and each poet even, has her or his lot, or share, of words. That is why, even if I do not regard them as my own ‘property,’ I think that certain words are/have become special to certain poets. And that is why I believe that a poet should write with few words. I look for these words in the works a poet has written (or even in the ones he has not written). In this way, I think, the poet would have to keep his grasp on his own issues, avoid wasting the accumulated vocabulary of another poet, and be ‘satisfied with his own lot.’ 3

Acceptance in humility appears as an essential element in Ergülen’s poetics, as does the very aspiration or desire (heves) to write poetry. Referring to ‘Mother’ (p. 10), the first poem in his earliest collection (Questions Without Response, 1982), which he wrote in memory of his friends who were killed following the military coup of September 12th, 1980, he says:

(This poem) aspires to raise a silent objection, if not resistance, to the inhuman practices of those days. ‘Mother’ is one of my most popular poems among readers, critics and poets. It can also be considered a summary of my poetry. As some critics have rightfully argued, the sound of my poetry has not changed much since those days and that particular poem. I can even maintain that it has not changed at all. The words and images I used have not changed much either: ‘mother,’ ‘child,’ ‘pain,’ ‘bird,’ ‘rain’ ... Throughout the years I added new words and images to these, but the new ones have not been that new, different, or as colourful. In a way, they are all colours that have a place in the same picture, images that can be thought of in the same framework. Here are some of the words and themes: ‘goodness,’ ‘grief,’ ‘love,’ ‘home,’ ‘brotherhood/sisterhood,’ ‘nature,’ ‘countryside,’ ‘balcony,’ ‘courtyard,’ ‘garden,’ ‘aspiration,’ ‘word,’ ‘letter,’ ‘friendship,’ ‘death,’ ‘body,’ ‘paper,’ ‘memories,’ and ‘poetry.’ 4

In due course, other themes emerge in his poetry, such as ‘pomegranate,’ ‘sea,’ and ‘provinces.’ ‘Pomegranate’ (p. 19), Nar in Turkish, makes its appearance in 40 Şiir ve Bir (40 Poems and One), which he began to compose in 1996 and which would win him three prestigious awards in 1997 and1998: the Behçet Necatigil Prize for Poetry, the Antalya Golden Orange Prize, and the Cahit Külebi Special Prize. A chapbook published concurrently carries the ‘summary of the first 42 years of his life in poetry’:

I was born on October 14, 1956 in Eskişehir as the first child of Nazlıgül and Hasan. My father was an auto mechanic, my mother a housewife. I had five more brothers and sisters. As a family, we were all kids, we all remained kids. I had my first schooling in Eskişehir, then went to high school in Ankara, where I also got my degree in Sociology from Middle East Technical University... I began writing short stories, about twenty of which were published in 1971-73, when I was still in high school and during my first years at university. My first poem came out under a pseudonym in a magazine in 1973. When I lost my closest friend Şahin (‘Lost Brother’, p. 30) in a railway accident, I went back to writing poetry, and that was it. My maternal grandfather, Hüseyin Efendi, was also a poet. He composed folk songs and sang them to his stringed instrument, the saz. I could neither sing nor play, I just wrote...’. 5

By 1998 Haydar Ergülen had already published five collections, having also assumed in the meantime two different authorial personae, evidently under Pessoa’s influence6. One is Lina Salamandre in a fascinating book composed of songs and letters presumably by Lina, a character ‘born of fire’ – Haydar Ergülen’s own invention – who gives voice to her passionate but unhappy relationship with Ruth Huntley (‘No One’s Closer to Me than Your Remoteness’, p. 13).

Ergülen’s other persona, Hafız, the poet, is a completely different character whose name instantly recalls the classic 14th century Persian Sufi poet, Hafız of Shiraz. In his biographical summary, Ergülen mentions Hafız simply as ‘a fellow whose poetry has been coming out in magazines for the past three years. He will soon be free of me in 1999 with a book of his own.’ 7 This book turns out to be Hafıza (Memory). ‘Love’s Inflection in Turkish’ (p. xii), which appropriately resonates with the origins and early tradition of Turkish poetry, is from this collection.

We may claim that more recently Ergülen has assumed a third persona, that of abdal: the traditional epithet given to wandering mystics or dervishes of Alevi belief, who sang their poetry to the accompaniment of their music. Here is how Ergülen contrasts their self-effacement with the glaring visibility of the poets of our day:

Once men went about delivering poetry yet remained unseen

they were the dervish, the abdal, the poet, dervish lost

abdal epithet, poet solitary, a bundle full of words, a chest full of spirit

they are no more, of no use, now is the time of the fierce dervish, trendy abdal, fresh shaman poet. With no single aspiration, with

not a thought for his lot, among the people yet against them

in shallow waters seeking depth in meaning, in royalty’s longboat

yet adrift with the others, he wishes to be seen not

as the oarsman but as the dervish by all and sundry.

Now poethood is visible. The poets have come into plain sight. 8

Ergülen’s hereditary roots and his early family grounding in the Alevî abdal tradition, find full expression in a recent long narrative poem, ‘Abdal Going Slowly on His Way’ (p. 100), which is included in our selection. Here the poet is shown to be on a spiritual and artistic journey, continuing the tradition in the path of his ‘sovereign,’ Hacı Bektaş Velî 9:

He’s my sovereign and comrade, my ongoingness

lifeless walls he rides driving them on and on

in a pigeon’s habit he flies, in a gazelle’s races onward

in a lion’s company has crossed this town often

it’s abdal who now slowly spreads

Hacı Bektaş Velî's paths

with the poems of his ongoingness:

Ergülen rules over this poem as Abdal, casting his own ‘modern’ vision into the mysteries and rituals of the Alevî bardic tradition, or ‘ongoingness’, as he puts it. Especially significant is the concept of ‘the Mother’ and various manifestations of femaleness not only in nature, but in human-made objects like ‘courtyard’ and ‘woodwork,’ as well as in thought and emotion, and in life experience, all of which celebrate creativity in the poem:

One born bears life, the tree bears life, and the courtyard

because all things start out female

feelings, images, poems, words

the leaf ’s female, water’s female, the apple’s female

sleep’s female, while dreams, I’d say, are angels,

I can’t vouch for the traveller, but the journey’s female

Ergülen believes that ‘a poem should have a mystery to it beyond a string of fine and meaningful words... I don’t know if the mystery involves a quest for truth, or if it involves being satisfied by some lack while achieving completion, or simply by leaving something out...’ 10

The sense of mystery In ‘Abdal Going Slowly On His Way’ permeates the whole poem, which concludes with the enigmatic lines: ‘between two eyebrows a mother has her seat / this poem doesn’t end here it’s only complete.’ In this narrative of a journey the reader can perceive the unique merging of Haydar Ergülen’s poetics and ethics.

Equally significant is Ergülen’s earlier poem ‘Pomegranate,’ in 40 Poems and One (1997), generally considered his poems of maturity, which he began to write the year before, when, as he puts it, ‘I married İdil. With her I opened out to 40 poems — out of the rooms onto the streets...’ 11. In an interview given in the same year, Ergülen states that he spent his childhood ‘more like an adult than a child, mostly reading books.’ So when he grew older he ‘fell in pursuit of his childhood, looking for it as his lost garden.’ Ergülen continues: ‘the dreams I had in my forties were very different from those in my twenties. Excess of words, ‘being literary,’ seeking depth in youthful angst, all that was gone, instead poetry became one of the most natural states of mind for me in trying to understand the world and humanity. Mature poetry seemed to arrive with clarity and precision.’ 12

‘Pomegranate,’ like ‘Abdal Going Slowly on His Way,’ holds a special place in Ergülen’s corpus of poetry. It is the only full poem about this fruit that reoccurs as the poet’s favourite among other fruits that appear in his poems, including the cherry, the apple and the olive. Here we see the full flowering of the pomegranate as a complex metaphor for home, garden and neighbours, living and sharing in fellowship. The metaphor expands, embracing the language of poetry as well as love, offering a poetic refuge not only from a winter of darkness but also from the ‘rough hand’ that could also destroy the ‘garden within garden’ of love and the poetry of ‘a thousand and one warm words of summer.’ Perhaps what ‘Pomegranate’ best signifies is Ergülen’s ethics of an ideal iyilik, which can best be translated as ‘goodness’ that also involves ‘healing,’ a state of mind celebrated more and more frequently in his recent poems.

‘Writing poetry is a form of goodness,’ runs a line in one of these poems (‘Form’, p. 76). ‘Poetry of Goodness’ is how Coşkun Yerli defines Ergülen’s work that ‘seems to convey the good-natured quality of a Turkmen dervish.’ 13 Another fellow poet describes him as ‘Working in the Store of Goodness,’ while yet another suggests that in 40 Poems and One, goodness dwells in peace with love, and the pomegranate is their home. 14

In ‘Pomegranate’ an essential point of reference is, again, Ergülen’s attachment to the Alevî-Bektaşî 15 tradition, which holds this fruit as a symbol of harmonious unity in plurality. Yet further telling references appear in such lines as ‘let’s head for the pomegranate.’ These echo the famous refrain of the ballad, ‘Let the Gates Open, Let’s Head for the Shah,’ by Pir Sultan Abdal 16, the legendary 16th century Alevî bard, who called out to his people to seek refuge with the Shah of Persia and join forces against the oppressive Ottoman governor in the East. Similarly, in the same poem, ‘If a rough hand enters the pomegranate’s garden’ harks back to another well-known refrain by Pir Sultan Abdal: ‘A Rough Hand has Entered our Friend’s Garden’, bringing destruction to his community. ‘Pomegranate’ is more than a poem about a fruit; it is a passionate warning against the deprivation of human values.

As readers will no doubt notice, Ergülen’s invocations and personal interpretations of tradition, which go back to classical Ottoman language and poetry (‘Translation’, p. 54), in no way confine the thematic richness of his poems but contribute to their diversity. Ergülen’s excellent command over the history of Turkish poetry, past and present, makes him a poet of poets, a believer in the fellowship of poets. This is revealed by allusions and explicit references to such leading figures as Cemal Süreya, Edip Cansever, Turgut Uyar and Ece Ayhan of the Second New Movement of the 1970s, but also to Atilla İlhan and Sezai Karakoç, from the older generation and to Seyhan Erözçelik, his contemporary, all of whom show up in this volume. Cemal Süreya is probably Ergülen’s favourite, the figure to whom he pays special tribute in ‘We’re Lonely, Brother Cemal’ (p. 25), and in his long, playful, autobiographical narrative, ‘On Things That Are Falling Asleep’ (p. 56).

As editors as well as participating translators, we have focused on offering readers the widest selection of Haydar Ergülen’s poetry possible in a volume of this size. Moreover, we have done our best to retain the richness of nuance and depth of meaning that characterise most of the work presented in these pages. For we believe that Haydar Ergülen deserves not only to be recognised as an original poet who has earned a position of distinction in his own country, but that his work proves him worthy of being ranked among the major writers in the world today.

— Saliha Paker

1 Baki Asiltürk, Türk Şiirinde 1980 Kuşağı, Istanbul, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2011. 147.

2 The Cunda International Workshop for Translators of Turkish Literature (CIWTTL, Türk Edebiyatı Çevirmenleri Cunda Uluslararası Atölyesi, TEÇCA (tecca.boun.edu.tr), which ran from 2006 to 2016, was supported by Boğaziçi University, Department of Translation and Interpreting Studies, and funded by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

3 From Haydar Ergülen’s talk in 2006 at the CIWTTL, partly translated by Şehnaz Tahir Gürçağlar for Aeolian Visions / Versions: Modern Classics and New Writing from Turkey. Eds. Mel Kenne, Saliha Paker, Amy Spangler. Milet Publishing, UK. 2013. 63-64.

4 Ibid.

5 Haydar Ergülen (40 Şiir ve Bir). Short autobiography in Andaç 1998. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı.

6 Haydar Ergülen, Preface to Hafız ile Semender. Toplu Şiirler 2. Istanbul, Adam. 2002. p.15

7 Haydar Ergülen (40 Şiir ve Bir). Short autobiography in Andaç 1998. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı.

8 From Haydar Ergülen’s talk (2006, CIWTTL), translated by Saliha Paker for this book.

9 Hacı Bektaş Veli (1281-1338), a saintly Sufi figure, legendary for his miracles, who is honoured by Alevî-Bektaşî socio-religious communities.

10 Haydar Ergülen (40 Şiir ve Bir). Short autobiography in Andaç 1998. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı.

11 Ibid.

12 Baki Asiltürk,Türk Şiirinde 1980 Kuşağı, Istanbul, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2011. 139-140.

13 Coşkun Yerli, ‘İyiliğin Şiiri,’ in 40 Şiir ve Bir Odağında Haydar Ergülen Şiiri. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı, 1998. 63,68.

14 Sina Akyol, ‘İyilik Dükkanında Çalışıyor Haydar Ergülen,’ in Haydar Ergülen (40 Şiir ve Bir). Andaç 1998. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı.

15 V. Bahadır Bayrıl, ‘Beyaza İltica Eden bir Şiirin Ana Aksları,’ in 40 Şiir ve Bir Odağında Haydar Ergülen Şiiri. Antalya: Altın Portakal Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı, 1998. 17-20.

16 Haluk Öner, ‘Haydar Ergülen’in Şiirinde Alevî-Bektaşî Geleneğinin İzleri.’ Unpublished essay.