Alys Morgan interviewed by Billie Ingram-Sofokleous.

Do not ‘abandon hope all ye who enter here.’

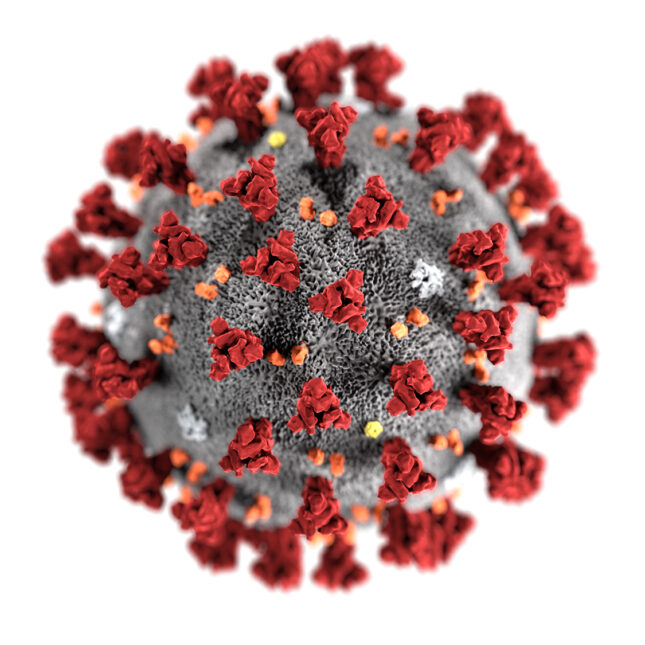

Ward Nine: Coronavirus, a heartfelt and informative journal of thoughts and feelings, is an absolute must read. In a minefield of overworked and underpaid nurses, overwhelmed cleaners, and a myriad of vacancies that need to be filled, when Alys Morgan was hospitalised with Covid she was nevertheless surrounded by kindness amongst the complaints, worries and unspoken truths. Her account of the wards is of a chaotic, yet safe space harnessed through the contemptible ailments of this disease. She recounts her daily journey into what could have been the abyss had it not been for the wonderful caregivers who bolstered her during her stay in hospital.

How did writing the memoir change your perception of the illness?

Before writing the memoir, I had not been in hospital for nearly thirty-five years. I realised how the NHS was under strain as a result of the illness. I also realised how it continues to operate with its most basic routines even when under strain and fighting a faceless enemy ‒ however stretched they were, the cleaner and the caterer came in three times a day. You always knew you were going to be fed. I also realised how diverse the illness was ‒ the version I had, which was gastric, was not even recognised at that time. I was diagnosed beforehand as having a gastric illness by both a GP and A & E, and they did not realise I had Covid till the results of the routine test came in.

What was your starting point for writing this memoir?

When I was discharged from hospital, I was given an excellent follow-up package, including weekly calls from physiotherapists and dietitians. I was also visited in hospital by a Mental Health Counsellor, who thought I would benefit from telephone counselling. I think this was because I could not cope, as somebody who had been a reasonably fit person, with what had happened to me, or what I had seen. I felt I could no longer cope with daily life or communicate with anybody who did not know what it was like to have Covid. My husband said I was mute when I came home and remained in a bedroom for six weeks. A MIND counsellor called me every Friday and encouraged me to talk.

In hospital, I had very little to do when convalescing. We were not allowed visitors, and there were no books or magazines as at this point they did not know if the virus could be spread via shared contact. So, I used to make very basic notes on the Ward's daily routine on Google Docs on my phone. I read these back to my counsellor, and she encouraged me to write them up. I did this on a daily basis, and read them back to my counsellor. This was the starting point for Ward Nine: Coronavirus. It was like writing a daily serial!

How do you feel lockdown affected the collective consciousness and changed what themes writers have been drawn towards highlighting?

I think we realised how easy it is to become isolated ‒ isolation has been a constant theme since lockdown began. You are alone on a hospital Ward, even surrounded by staff. You are alone when shielding at home. A lot of telephone befriending schemes have been set up in Wales to help with this. Then there's our own mortality. We tend to think we are immortal, that the NHS can cure anything, that we can be vaccinated against anything. In the early days of the virus, people died, and we became aware of our own mortality. I think there's also the kindness of strangers ‒ whether hospital staff, or a telephone befriender. And the depression we can suffer as a result of isolation, separation, illness, and anxiety. And how we coped with a lockdown situation ‒ we do know there were people who broke the rules. And how you cope with relationships in time of lockdown ‒ whether in close proximity or separation.

Who gave you the most support while writing this?

The MIND counsellor who telephoned weekly and read the draft text. And at a later stage, the editor from Parthian, who made all sorts of helpful suggestions. A lady at the Wales Book Council, who suggested how to find publishers who might be interested in it. I didn't actually write for publication ‒ it was creative writing therapy. It was raw writing about a raw experience.

What was the hardest part to write for you?

All of Ward Nine was hard to write. When I began it, I would lie in bed (where I wrote it), gazing at a blank screen, and forcing myself to write it. I set myself a goal of writing so many words a day. I think that this was partly because the experience was so raw ‒ in fact, my husband and some of my friends still cannot bring themselves to read the book. They say reading of my suffering is too much for them.

Probably the hardest part to write was the naso-gastric feeding experience. This was when I realised how ill I actually was and how desperate they were to find an effective treatment. It was also the time I realised I could never have been a suffragette! But it was also a turning point.

It was also very hard to write of death on the Ward, at a time when patients died without being able to see any of their family. Death is something we know is coming for all of us, and we always hope it will be surrounded by loved ones, which doesn't happen on a Covid Ward or in ICU. Death was in fact like a constant presence on the Ward, indeed in the entire hospital. You became aware of this when you saw the morticians. At this time, they were using white sheets as there weren't enough body bags, and had erected scaffolding in the morgue for the dead bodies.

Who is your biggest inspiration?

As I said before, we had no books or journals in the hospital. When I felt well enough, I would look on my phone for reading matter, usually poetry or Project Gutenberg. One day I was lying in bed, and I remembered reading Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year, which I had not read since I was at University forty-five years ago. I found it on Gutenberg and read through it in a day. I was stunned by the parallels with our own time, which are quoted in Ward Nine. It's also a cracking piece of I Was There journalism. That was the real inspiration for Ward Nine. I realised we were living history, and that the experiences of ordinary people needed to be recorded ‒ staff and patients. That ordinary people were doing extraordinary things.

When you are in hospital, you also feel very close to the dead, who are as real as the living. I felt very close to my long-gone parents. I used to think a great deal of my mother's experiences during World War Two ‒ she worked in a munitions factory in a heavily blitzed Birmingham, and would go home at night to a night of air raids. She said she had not done anything particularly heroic ‒ she simply survived and went from day to day.

Other books I found inspiring were John Wyndham's Day of the Triffids (I heard it discussed on radio the other night) and Albert Camus' The Plague (which became a bestseller last year). I also read Alexander Solzhenitsyn's Cancer Ward.

Another book I found inspiring was Betty Macdonald's The Plague and I. Macdonald was a bestseller in her day but is virtually forgotten now. She wrote humorous autobiographies, but The Plague and I is much darker. It's an account of her year on a tuberculosis ward in the USA at a time when TB was highly infectious and virtually incurable. Macdonald caught it from a co-worker at her place of employment, and her employer refused to put any safety measures in place or admit blame. Her initial worry, till she was admitted to a charity hospital, was how she would pay for treatment ‒ making you realise how invaluable the NHS is. She observes in detail the daily routine of her ward, and how you are thrown in close proximity when ill with strangers, whether patients or staff ‒ the unexpected relationships that arise as a result. How you are separated from your closest family when you have an infectious disease. The sudden presence of death. The writing can seem out of date to us, but it's an interesting read.

Since leaving hospital I have also read Michael Rosen's two Covid memoirs, Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS, and Sticky McStickface.

Your use of Matthew Arnold and Daniel Defoe's work peppered throughout is stark and painful as you relate the similarities in such a remarkably eloquent way; did you cry as much as I did while reading?

I only cried twice in hospital, although often close to it. I cried after the naso-gastric feeding episode, when I told one of the nurses I had had enough and wanted to die. Then I cried on the day I left when the nurses clapped me off the Ward.

I think I felt frozen in emotion much of the time ‒ that if I broke down, I might not make it.

I also felt that I needed to be an impartial observer ‒ I felt a bit like Christopher Isherwood, that I was a camera, recording for posterity. The kind of history that is important is not always that written down in the history books. The stories my mother told me of life in World War Two were not what we studied at school. That I had to write the story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

I did cry when I watched Michael Rosen's story on The Story of Us on ITV, and listened to The Reunion: The Covid Ward on Radio Four. And also, when I read Rosen’s, These are the Hands, written for 60 years of the NHS, but so relevant to Covid. It's what Blanche talks about in A Streetcar Named Desire, about relying on the kindness of strangers.

I cry when I think of the dead and read their families' stories ‒ in particular the NHS staff who died on the front line.

Did you experience a new sense of fearlessness, or did you become more cautious as a person after this experience?

I stayed in my bedroom for six weeks after I came home, and went back to work in September. At first, I did think I was immune to Covid, but this quickly faded. I did find I was paranoid about social distancing, one-way systems, and masks, and I couldn't bear to be in a very crowded place, such as a supermarket. I'd been surrounded at work for years by people with colds, and now it terrified me when people coughed and sneezed. I've been there, you see. I know what it is like. I saw people die.

Did writing this open up any wider questions about yours and your family’s mental/physical health?

I am nearly sixty-five and I come from the stiff upper lip generation ‒ we were never encouraged to speak of our inner emotions, and there was no such thing as mental health counselling.

I think Covid acted as a catalyst which split open fissures in me and my family ‒ you did realise that there were issues that needed to be dealt with and talked about ‒ relationships, environment, emotions.

I also now suffer from Long Covid, which has physical and mental effects. The long-term effects of Long Covid are still being monitored. I think we'll be living with this for some time ‒ like rationing after World War Two, or PTSD.

I now have great admiration for the work of such organisations as MIND and the Samaritans, especially since they are so dependent on volunteer help.

What would your younger self say about your experience or mindset in hospital?

I hadn't really spent much time in hospital since I'd had my tonsils out aged seven! I think I was impressed how the daily routine of a hospital goes on irrelevant of the fact that they were fighting a virus which was then incurable ‒ the cleaning, the catering, the daily rounds by the consultants, the taking of temperatures and blood pressure. Their cheerfulness and endurance.

I realised I was not a good patient. Sickness does not necessarily make you saintly. I was bitter and resentful about being ill. I was reminded of Dylan Thomas's poem ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’. That when ill and dying, we can be angry. The staff coped wonderfully with this, compassionate and detached at the same time.

Never think it can't happen to you. Value the NHS. Fight for it. Be grateful.

Alys's book is available here